Brian Abbey, Managing Director, International Tax Services

Jim Swanick, Managing Director, Federal Tax Services

On March 27, President Trump signed the $2 trillion bipartisan Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (H.R. 748). The following article highlights some of the key corporate income tax refund and savings opportunities in the CARES Act, along with the U.S. international tax issues which also need consideration and could reduce refund and savings opportunities.

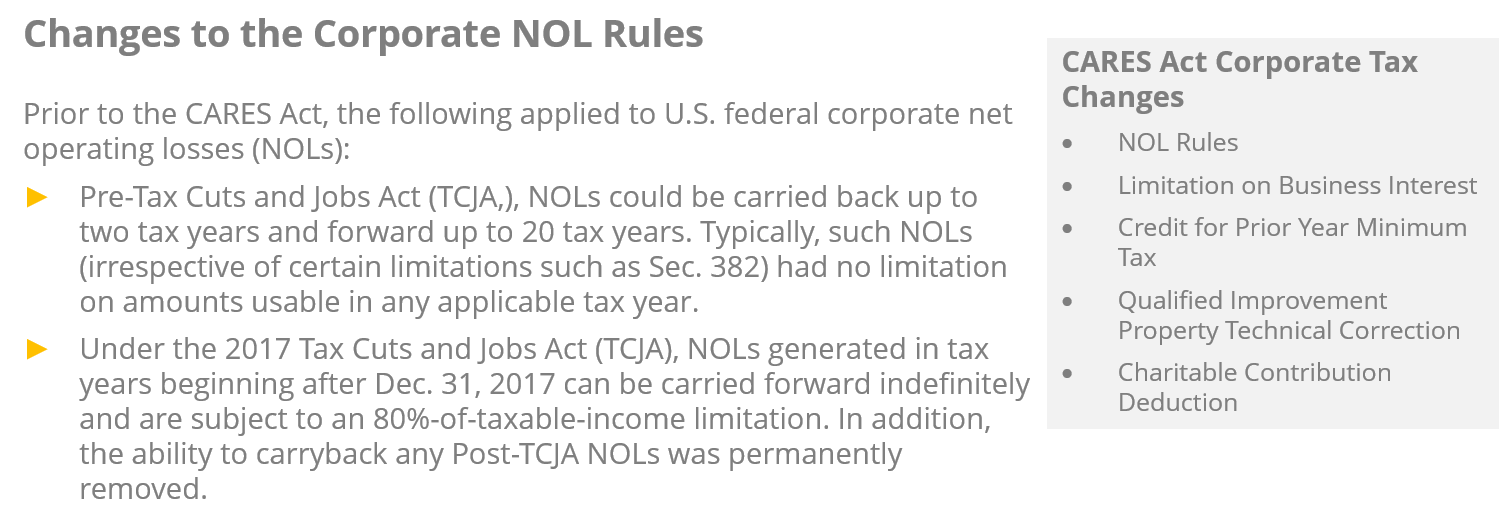

The CARES Act made the following changes to the NOL rules:

Rule: For net operating losses (NOLs) generated in tax years beginning after December 31, 2017 and before January 1, 2021, taxpayers can carry such losses back to the 5th year preceding the loss year. Like old NOL rules, taxpayers can elect to forgo the carryback period and instead carryforward the NOLs to subsequent periods.

- Refund Opportunity

Corporations with losses in 2018, 2019 and/or 2020 can now take advantage of the ability to carry these losses back to 2013 and subsequent years, resulting in a 35% tax benefit for such losses rather than a 21% benefit if such losses were to be carried forward. Companies will want to carefully consider the full impact of such carryback to clearly understand the effect on various calculations in those carryback years. For example, a carryback to 2018 or 2019 could require a recalculation of various taxable income limitations applicable in the carryback year, such as the section 250(a)(2) limitation on the global intangible low-taxed income (“GILTI”)/foreign-derived intangible income (“FDII”) deduction and the impact on the Section 199 Domestic Production Activities Deduction (DPAD), various general business and foreign tax credits, and the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT).Taxpayers may also want to consider filing accounting method changes for either 2019 or 2020 to accelerate deductions or defer revenue and increase the NOLs in those years to maximize the carryback opportunity. Alternatively, a company may want to consider reverse accounting method planning to increase taxable income in 2019 or 2020 if it has expiring pre-TCJA NOLs or tax credits.

- Commentary

If a taxpayer elects to claim a foreign tax credit, a NOL must be sourced among the taxpayer’s foreign tax credit baskets. The result of a NOL carryback is that it becomes a deduction to the net income in that basket in the year which the NOL is carried back to. The effect could be that a taxpayer creates foreign tax credit carryovers. Companies will be confronted with realizability issues related to this new deferred tax asset for purposes of financial statement reporting. It also may be possible that a NOL carryback generates an overall foreign loss, an overall domestic loss, or separate limitation loss. This analysis can be complex and the foreign tax credit ripple effects should be quantified before concluding on how a taxpayer decides how to manage their NOL situation. A NOL carryback can also cause taxpayers to have a base erosion and anti-avoidance tax (BEAT) liability when they did not have one on their original return. This situation may arise, for example, if a NOL carryback to 2018 or 2019 reduces the taxable income and tax liability significantly from the original calculation. In addition, if a portion of a NOL consists of a base erosion payment the base erosion percentage of the NOL gets added back to the modified taxable income calculation. Although the structure of Section 59A and corresponding regulations contemplates a NOL carryforward only, it is likely that the IRS will issue guidance that says a 2020 NOL that includes a base erosion payment will be subject to the same rule if that NOL is carried back to 2019. Companies will want to carefully consider whether this could impact any non-consolidated controlled group members where a portion of the carryback is BEAT-tainted resulting in the controlled group going from not being subject to BEAT to now being subject to BEAT. However, note that a carryback to a pre-TCJA tax year where BEAT does not apply may remove the BEAT-taint entirely which could be very beneficial to certain taxpayers.

Rule: The CARES Act temporarily suspends the 80%-of-taxable-income limitation on the use of NOLs for tax years beginning before January 1, 2021, thereby permitting corporate taxpayers to use NOLs to fully offset taxable income in these years regardless of the year in which the NOL arose.

- Refund Opportunity

This would allow, for example, a 2018 NOL to be carried forward to offset 100% of taxable income in 2019 or 2020 instead of only 80%. Or alternatively, such NOL could be carried back to tax year 2013 and subsequent years to offset 100% of taxable income in such years. Companies will need to carefully model out the various alternatives to determine the best option to meet their specific objectives.In addition, to the extent NOLs were limited in 2018 (due to a short period filing) or 2019 under the 80%-of-taxable-income limitation, companies can consider revising or amending returns for such years to take advantage of the suspension of the 80% limitation.

Rule: The 80%-of-taxable-income limitation would be reinstated for tax years beginning after December 31, 2020. This applies to NOLs arising in tax years beginning after December 31, 2017, including those generated in 2018, 2019 and 2020.

- Refund Opportunity

This provision may put additional pressure on the need to utilize the 2018, 2019, and 2020 NOLs through either a carryback or prior to 2021. The post-2020 reinstated 80%-of-taxable-income limitation is to be calculated- based on 80% of taxable income after the use of pre-2018 NOLs, and

- before the Section 250 deduction for FDII and GILTI. Calculating taxable income without regard to deductions under section 250 for purposes of the 80% limitation is likely to be favorable to taxpayers whose Section 250 deductions are not expected to be income limited, but unfavorable for taxpayers whose Section 250 deductions are limited.

- Commentary

Under the pre-CARES Act rules, one common interpretation of the 80% limit was to apply the limit to taxable income before any NOLs including pre-TCJA NOLs. This generally resulted in a higher limitation. The CARES Act clarified that the 80% limitation is applied to taxable income after the use of pre-TCJA NOLs, which will generally result in a lower limitation. Note, however, that the 80% limit is suspended for years beginning before January 1, 2021 so this provision will not apply until 2021.As mentioned above, the rule requiring application of the 80% limit before the Section 250 deduction can be favorable or unfavorable depending on the fact pattern. Although taxable income may be reduced in most situations due to the increased NOL limitation, it may come at a permanent cost of a lost Section 250 deduction for a company whose Section 250 deduction is income limited under Section 250(a)(2).

Rule: Companies with a tax year beginning before January 1, 2018 and ending after December 31, 2017 are now eligible to carry such loss back two years and forward twenty years consistent with pre-TCJA law. Previously, such losses could not be carried back. Affected taxpayers are given 120 days after March 27, 2020 (to July 25, 2020) to file an application for a carryback of that loss, or to elect to forgo the carryback.

Rule: Where a 2018, 2019, or 2020 NOL is carried back to a 965 Inclusion Year, the CARES Act deems taxpayers to have made the section 965(n) election to “waive off” the use of NOLs against the taxpayer’s transition tax inclusion. Thus, such NOLs cannot offset the deemed income inclusion under Section 965, which occurred in 2017 for most taxpayers.

- Refund Opportunity

Although any NOL carrybacks are specifically excluded from a taxpayer’s Section 965 amount, the CARES Act does not seem to limit using additional foreign tax credit carryforwards generated from a NOL carried back to a pre-2017 tax year in reducing the Section 965 liability. - Commentary

Companies can elect to skip the transition tax year altogether. This election may be especially beneficial to taxpayers who have a foreign source NOL. If the election were not made in that scenario, the ability to claim a foreign tax credit in the transition tax year could be significantly limited. Even if the NOL is 100% U.S. source, it may reduce foreign source income to the point that claiming a foreign tax credit is still difficult. These facts may create an Overall Domestic Loss (ODL). But if a cash refund is the purpose of the carryback, consideration should be given to this election in order to maximize the cash refund, even if this means forgoing a positive attribute like an ODL. It also provides companies an opportunity to increase foreign tax credit carryovers though NOL deductions in pre-2017 years.

Changes to the Limitation on Business Interest

Prior to the CARES Act, and for years beginning after December 31, 2017, corporations could deduct business interest expense under Section 163(j) up to the sum of:

- Business interest income for the year,

- 30% of adjusted taxable income (ATI), and

- the companies floor plan financing interest for the tax year.

Business interest in excess of this limitation can be carried forward indefinitely. For tax years beginning after December 31, 2018, the CARES Act made the following changes:

Rule: For years beginning in 2019 and 2020, the 30% limitation on ATI for corporations is temporarily increased to 50%. However, companies can elect out of the 50%-of-ATI rule if, for instance, they are trying to preserve expiring tax attributes.

- Refund Opportunity

Since 2019 and 2020 NOLs can now be carried back five years, companies may be able to increase their 2019 and 2020 losses under this provision to maximize the benefit of the carryback to a 35% tax rate year.For tax years beginning in 2020, companies can elect to use their ATI from their last tax year beginning in 2019 for their ATI in the 2020 tax year. This rule, in effect, allows companies to use the higher limitation of the two years especially since 2020 may be substantially impacted by the current economic environment. This could put additional attention to maximizing ATI in 2019 since it could potentially be used as the 2020 ATI amount if beneficial.Both elections have implications beyond just increasing their interest deduction, primarily given the interplay with the international provisions of the Code. If not quantified appropriately, companies may inadvertently hurt their cash tax position.

- Commentary

Because Section 163(j) applies to Controlled Foreign Corporations (CFCs), the Section 163(j) elections (using 50% EBITDA and to use 2019 income) in the CARES Act will affect CFCs as well. These changes can lead to the deduction of significantly more interest expense at CFCs, decreasing tested income/GILTI and Subpart F income, if applicable. In some situations, this reduction can have a negative impact to the ultimate U.S. parent. If the taxpayer did not make the CFC group election in the Section 163(j) proposed regulations, they are probably including GILTI and Subpart F income in their own 163(j) calculations. These amounts would be reduced. Alternatively, if the taxpayer did make the CFC group election, the increase in deductible interest at the CFCs could decrease the CFCs’ excess taxable income available for the U.S. parent to use in calculating the U.S. group’s adjusted taxable income. This amount could drop significantly due to the tiering up rules of Section 163(j) from lower CFCs to first-tier CFCs as required in that calculation.Additional interest expense may also reduce Qualified Business Asset Investment (QBAI) to the extent it is considered specified interest expense. In other words, the CFCs are paying interest to a party outside the U.S. parent’s group. This interest expense will reduce the QBAI return in calculating the net deemed tangible income return.If the U.S. group is eligible to deduct more interest expense under either election, it could have an adverse impact to the foreign tax credit limitation as more interest expense will be apportioned, further reducing foreign source income. In the case of general or branch baskets, the taxpayer will end up with a foreign tax credit carryover. The GILTI basket attracts the most interest expense for most taxpayers, and when combined with the “use it or lose it” nature of GILTI basket taxes, it is easy to see problems arising with higher interest deductions. Any additional interest expense in the GILTI basket will cost taxpayers, as anyone who has gone through this exercise in 2018 already knows. Any benefit from making the taxpayer favorable elections could be reduced by forgoing foreign tax credits in the general basket and the GILTI basket specifically.In a related analysis, additional interest expense could also reduce Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII) benefits. This occurs because of the requirement to allocate and apportion interest expense against foreign derived deduction eligible income (FDDEI). Because FDDEI is the key variable in the FDII calculation, any reduction to FDDEI ultimately reduces FDII. Like the foreign tax credit, increasing Section 163(j) limitation may not provide a dollar for dollar benefit as other favorable tax items may claw some of that benefit back.Even U.S. source interest expense may cause a problem. The increased interest deductions may cause FDII and GILTI to exceed total taxable income. In this scenario, the Section 250 deduction is limited to the excess, divided proportionately between FDII and GILTI. This result is not favorable as the company is exchanging a permanent benefit for a temporary benefit. The cash needs of the business may dictate this choice more so than the “permanent vs. temporary” aspect, but companies should carefully consider this tradeoff.If the U.S. group is making base erosion payments, then like a NOL carryback, the reduction to taxable income could negatively impact the BEAT position. The reduction to taxable income will ultimately reduce the U.S. regular tax liability thus potentially putting companies in a BEAT position or increasing a BEAT liability which already existed. Alternatively, increasing the denominator with additional interest deductions, especially if the interest is to an unrelated third party, may drive down the base erosion percentage, resulting in BEAT to no longer being applicable.

Changes to the Credit for Prior Year Minimum Tax

The TCJA repealed the corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) effective for tax years beginning after December 31, 2017. Transition rules allowed corporations to utilize their remaining minimum tax credits (MTCs) over several years, ending in 2021.

Specifically, for tax years beginning in 2018, 2019 or 2020, corporations could receive a refundable credit equal to 50% of the excess of the MTC for the tax year over the amount of the credit allowable for the year against regular tax liability. Any remaining MTCs were fully refundable in 2021.

The CARES Act accelerates the ability of corporations to benefit from any remaining MTCs they may have. Instead of allowing a 50% credit in 2018 through 2020, with a 100% credit in 2021, the legislation now allows a 50% credit for 2018 and a 100% credit for 2019. Alternatively, a taxpayer may elect to claim the entire refundable credit for 2018.

- Refund Opportunity

Rather than filing an amended 2018 return to claim the credits, the CARES Act allows the taxpayer to file an application for a tentative refund (quickie refund) by December 31, 2020 to claim its remaining MTCs for its 2018 tax year. This form can be filed immediately to accelerate to refund. Alternatively, the taxpayer can claim its remaining MTCs on its 2019 return. For taxpayers that have already filed their 2019 return, they may be able to file a “superseded return” to claim the unclaimed MTCs if such return is filed prior to the return’s extended due date.

Qualified Improvement Property Technical Correction

Qualified improvement property (QIP) is defined under Section 168(e)(6) as any improvement to an interior portion of a nonresidential building that’s placed in service after the date the building is first placed in service — except for any expenditure attributable to the enlargement of the building, any elevator or escalator, or the building’s internal structural framework.

The CARES Act adopts a technical correction to the TCJA’s apparent oversight in excluding the eligibility of QIP from eligibility for bonus depreciation (i.e., currently 100 percent). The law changed the recovery period for QIP to 15 years, thereby enabling it to qualify for immediate expensing. As this technical correction is effective as of the enactment of the TCJA, taxpayers are required to change the depreciation methods of QIP placed in service after 2017 that would have been depreciated as 39-year building property.

- Refund Opportunity

Although additional guidance may be needed, taxpayers should generally be able to change QIP depreciation methods by filing an automatic accounting method change. However, if a QIP asset was only depreciated on a single tax return—e.g., it was placed in service in 2018 and the 2019 return has not yet been filed—the asset’s depreciation method may also be corrected with an amended return.Companies should carefully analyze property acquired in recent asset acquisitions to determine if QIP was acquired and whether such property can be immediately expensed. Although this rule presents a significant opportunity to maximize losses in 2018-2020 which can then be carried back to obtain cash refunds or reduce taxes paid, caution should be exercised to ensure the property qualifies as QIP as defined in Section 168(e)(6), as not all real property qualifies for this classification. It is also important to note that after 2021, depreciation is no longer added back in calculating ATI for purposes of Section 163(j) so choosing to take bonus depreciation for QIP could have a detrimental impact on the Section 163(j) interest limitation.

Modifications to the Charitable Contribution Deduction

Modification of limitations on charitable contributions during 2020 will allow corporate taxpayers to deduct more of their charitable contributions by increasing the taxable income limitation from 10% to 25%. There is also an increase to the limitation on deductions for contributions of food inventory from 15% to 25%.

Conclusion

As you can see from above, the CARES Act offers corporate taxpayers many opportunities for the potential recovery of prior year tax payments to help improve cash positions. Careful consideration should be given relative to your company’s specific fact patterns. GTM is here to ensure that your company is prepared. Contact us now if you require assistance to address CARES Act refund opportunity modeling or filing support.